Overtime Vs Productivity 02

| Is it worth it working extreme hours all the time, day in day out – more importantly are you actually getting that much done during that time? |

| Foreword |

| Since the first half of this article came out, a few things happened. The article was really well received and circulated through almost every major studio in LA, London, Sydney, New York, everywhere. I received more than a hundred emails which were almost entirely positive, surprisingly not only from artists but also from studio owners, producers, supervisors and alike. The article was translated into Spanish & Japanese and distributed further and a lot of interesting stories streamed in over the coming weeks about various radical changes and new work protocols.

For those who have not read the first part, please click here Now, there were a few people who did misinterpret the meaning of the article, and I expected that. I did receive comments about “You’re right Allan, this industry sucks, we’re worked too much” which wasn’t really the point of the article. I think that that’s entirely up to you whether you want to put up with OT and bad working conditions. But the stories that have come in about changes to studios have been really rewarding to hear about.One of my favorites was actually one I witnessed first hand which a studio I was at arranged for a lady in a pink ape suit to come in and sing her own variation of You are my sunshine to everyone in the studio to boost morale, the lyrics I’m not sure if they were specifically customized to us but basically were that we’re appreciated for our hard work and efforts and keep up the great work. Now I thought this was great, as it really takes peoples minds off of work and gets everyone to laugh for 5 minutes, and probably costs $150 to arrange. Plenty of people have contacted me to say that there has been drastic changes in day to day work, as well as how they handle a lot of their planning and scheduling etc. How to treat their team and reward them to keep morale up etc. |

| Overtime vs Productivty Pt. 2 |

| The reason this article was set in two parts, was to put some focus on ways to work more productively through less work by just applying some core rules to your day to day work life. However the second half, this article is aimed more at looking how artists themselves can really step up and take more responsibility for the productivity in the workplace. Work faster and more efficiently, and explore ways to inspire themselves to be better at what how they handle themselves day to day.

Evaluating your own daily productivity Although it is easy to blame management for having to stay back to finish up shots, I think what is really important is for everyone to also look at themselves and evaluate how much work they are getting done day to day. What if, a typical day consists of the artist coming in at 10am, checks email, gets a coffee, catches up with buddies, by this stage it’s 11:30am and then they check their renders and do some work, and then head to lunch, after coming back from lunch at 1pm, browse web and email while their food settles. And then resume work til 3pm coffee break, also game or two of ping pong or whatever else work til 5:30 and head home. This of course isn’t everybody, and every work environment and individual is different, however in this scenario if we look at how much work got done in a 10 hour day it’s really closer to 5 or 6 hours per day of actual work. Of course noone is expected to be glued to their screen, and I honestly think it’s far more healthy to have breaks and be relaxed. I tend to get a lot of my work done when I’m away from the computer sitting on a couch with my eyes closed (I’ll get to this) but it is important to first of all be aware that if you think it is unfair to work late hours, then you must also look at how much time you are actually getting work done throughout the day.There’s an interesting TED talk by Jason Fried on Why work doesn’t happen at work which brings up a lot of valid points on why most of the time while we are at work we aren’t really getting that much done, and it’s more why we end up going home to get work done, and similarly why most of are “ah hah” moments are probably on the toilet or our drive in to work. This is because we have far too many distractions AT work, in addition to meetings, and various other productivity stoppers. In 1991 H. Randolph Thomas did a case study on effects of scheduled overtime on labor periodically. What’s interesting is that for such a common subject as overtime, there really isn’t much data to track what is productive and what is destructive, and therefore there is no major case studies to demonstrate how destructive this can be. Effects of Scheduled Overtime on Labor Productivity Calculating Lost Labor Productivity The more you reflect on yourself day to day the better you’re going to be at being productive. I regularly look at what I did each day and if I could have worked better, and if I did do something right then how to replicate that more often. The same reason we have post mortem meetings to evaluate how a project went, I will regularly look at what I am doing and how I can work faster and more effectively. Also I look at common problems that happen and how I can avoid them. I plan my days quite thoroughly before they begin, and I really focus prioritizing my tasks and communicating with the people around me. All of these things make for more efficient work. If I don’t think for some reason I will deliver on time, I do not wait to the last minute to let people know, I raise my hand right away so we have time to change our plans. |

| Parkinson’s Law |

Something to live and die by is Parkinson’s Law. This really applies to your work day to day, but also sadly it can apply to the reviewing process of getting shots approved if clients have all the time in the world! http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Parkinson%27s_Law When you need to deliver for a deadline, usually you’re able to pull absolute miracles – knocking out work faster than usual, paying attention to what’s going on, chasing up renders to the compositors as soon as they’re ready, and checking if they need anything else. You’re really on the ball, making sure everything gets done. Most of the time we do not all work like this, however when we do, it’s amazing how much we get done. And this essentially is Parkinson’s Law. What if you work like this all the time? I try to as often as I can, I usually have one goal in my mind when I walk into work in the morning, and that is to try to get out of work on time. So I am usually working as fast as I can and hard as I can. |

| Identifying Time Wasters |

| Between facebook, email, frequent coffee breaks, browsing the web and checking email, there’s a lot of downtime throughout the day. Some of it is necessary, some of it could easily be avoided. Same goes for meetings and other things that take up a lot of time and can quite a lot of the time be avoided too. There are definite time consumers.

It is unfair that artists get asked to work late hours to meet specific deadlines, and usually are not compensated for this. However, at the same time, most CG work places tend to be pretty relaxed most of the time, and sometimes this encourages people to get a little too relaxed with their time. The reason I wanted to write a second part to this article was because as I previously mentioned, there’s two sides to a coin. Personally one thing that I notice a lot when I look at almost any person, whether they are in the vfx industry, or whether they are in banking or literally any field is what sets the more successful people apart from everyone else, who do great at their job but just do not have that extra “thing” that sets them aside. What I realize, is that those who really accel at what they do, usually are the ones who have more motivation and hunger to succeed. Not only in their work, but generally day to day in their life. The reason I bring this up, is because I think that everyone really needs this, and that is to look at ways to do things better, faster, more efficiently. I tend to make this a game day to day, looking at ways I can work more efficiently and get my work done, looking at understanding at the end of a project, what worked and what didn’t work on it, and how we or myself can do things better next time. I think this is a positive outlook to have and you begin to look at almost everything a little differently.

|

| After I submit a render do I A) go play ping-pong, B) go get a coffee or C)…. WORKFLOW TIPS |

| Every time a render is completed, check your renders. This is important, and might take 3 minutes to load, but can save you a lot of grief. If you just forward your renders on saying that they’re done, then you’ll look stupid later when there are render issues, but more importantly if they are submitted and the compositor and no one checks them until right before the deadline, and at this stage the renders ARE incorrect, then you will have had all of this time to check your renders and fix the mistake before it became a big deal. This is also why I say comp your work. It might mean you do not have to do more work as you realize that the stuff you’ve done so far is sufficient and there’s no need for excess amounts of layers etc. But also it lets you see your alphas and how things blend together, as a big and common mistake is holdouts rendered with alphas etc.

If you find issues with your renders, and then go and fix them right away – then its not as bigger deal. Producer asks why your stuff isn’t there yet you can say “I noticed a is take in the renders, I’ve fixed the is take it is now re-rendering it will be done soon” this shows initiative, you’ve gone and fixed the issue without anyone else needing to detect it. This is better than them coming back and saying your renders are wrong. Or like I mentioned, finding out after it is too late. Usually I will submit a render, and then go and do a test render of a single frame, at least now my render is on the farm so it’s doing it’s thing, but then I can basically render a single frame that might take a few minutes to render, but at least then it will tell me whether I might have rendered with the wrong render layers, or there’s issues with the alphas, or other things that I mightn’t have picked up. If your renders are pretty intense, you can always turn off GI and motion blur, reflections and other things that are likely not going to stop you from viewing noticeable errors in your render. If I do in fact find a problem, then I can simply kill my render and re-submit it. This is important as it saves time, and also if you are rendering something that is incorrect, it’s better to kill it sooner so the farm isn’t wasting precious cycles that another artist could be using. I will usually keep an eye on my renders too, that way if they are erroring out, then I can notice ahead of time, rather than waiting for someone to tell me after it has been crashing the farm for a good hour by starting and quiting my jobs. Also when 10-20 frames are rendered, I will try to check those rendered frames as a way to check whether my renders do in fact look correct. These all might seem like a lot of work, but honestly they’re all background tasks that you can do while you are working just to keep an eye on things and make sure your work is in fact rendering correctly. |

| Be your own manager |

| This might have come from running a studio for so long, but any time I am physically working on FX shots myself, I tend to keep an excel sheet of every shot I’m working on, and it’s status. I also have another individual excel sheet for every single shot of mine. I will basically write up a template of each, and then all the statuses along with a color for each, and then it’s easy for me to copy and paste different statuses as needed, to change things on the fly.

This again might seem like a lot of work, but in fact it’s so easy to work this way, and it saves me from having to store too much information in my head, or leave room for making mistakes. Because I update this excel sheet with where my shots are at, and continue to go about my day. Also if compositors or producers need to know the status of my work, they’re able to just load up one of these sheets and look. Compositors will love you for this once they get used to your process, and producers with LOVE you for this, because essentially you’re speaking their language. |

| Going down the right path the first time |

| A lot of people tend to be scared to show their supervisors their work, because they’re afraid of revisions, so they figure if they hide it long enough then there won’t be time for revisions (or maybe that’s just me that does that?) The fact is that it’s far better to open up the doors of communication sooner, show stuff at the very beginning, or better yet spend a little extra time to punch out a few variations of what you’re doing in very crude form, and get the exact direction you need to go before you really spend a lot of time on it. If I’m working as an artist I tend to start painting up concepts or basic animatics right away, and get feedback, and communicate what I intend to do so we are all on the same page. This way I go down the right path the first time, and there’s no room for error. And again they have more confidence in you because they see and understand your process.As I mention elsewhere in this article, communication is really key. And the more you speak with confidence and on the same level as those people around you, the more you will be respected and your opinion trusted. Learn to communicate and be able to successfully communicate your ideas to others. This is key.

|

| Multitasking = bad |

| I hear constantly how busy people are and how they’re doing 50 things at once, this isn’t necessarily being productive but rather distracting yourself from ever actually getting anything done. Have you ever spent a day doing a lot of random things, and at the end of the day you have nothing to show for it? It’s probably the most common thing to do, have a few web browser windows open, databases, email etc. and rather than focusing on one thing and getting it done, you devote all your time to getting everything 5-10% further.The real solution to this, is to prioritize your work, figure out what needs to be done first, and do it. And then introduce a more productive method of multitasking, which is lets say with VFX, once one shot is rendering, jump onto the next, or once you’re waiting for a response to some of your emails, jump onto the next big task. But the idea is to see things through, and this way your brain is able to focus on one solid task too, rather than it trying to vaguely keep up with all the different things you have going on.

I am a victim of this at times, and it’s amazing when you finally sit down with a list and start checking things off, that they actually DO get DONE!

|

| Make a plan of action |

| What you really want to do is plan your day, write down on a piece of paper everything you need to do that day. By writing it down it’s there, it’s physical and it means you can’t forget it, or mix up your priorities. It’s a constant reminder and it also means you have a plan. The next step, is to prioritize these things.

Essentially you want 2 primary goals you need done, and then you will put those that are really crucial for that day on a side list. This might be emails you need to send, chores like going to the post office etc. But group all of these up so that you’re doing them in a more affective manor. Ie. if you have several phone calls to make, and emails to write, errands to run out of the office, group them together. Notice how you’re able to knock emails out faster when you’re writing lots of them? Rather than writing one and then making a phone call and then writing the next, or constantly ducking out of the office all day long when you can get most of it done in one trip. The idea is to group things together, but more importantly get rid of them so you can have a longer period of focus on your main 2 primary tasks. [ Simple, but effective – yet most people remain unorganized] The idea here is that you want to be in the zone, you want to be able to focus for a solid 3 hours at least, each day on one or two major tasks, and see them through. So that day you write down the two major things you want to achieve, and you set out to get those done. Everything else is secondary and should be done in your downtime, ie. do not start writing those emails you listed on your list to write, while you are animating or comping your shot. Wait until the shot is submitted for review, and then go do these things. Or better yet, come in earlier and get those things done and out of the way so they’re not your problem anymore. Now how can you tell if you have written too much on your list of things to do? Here’s an interesting thing to try. Write down a realistic and slightly generous amount of time it will take to do each task. Writing an email is usually a 5-10 minute task, but creating a fireball for a specific shot could be 5-6 hours, phone calls can sometimes go for 30 minutes etc. So if you have 5-10 things on your list, you might soon realize you have 2-3 days worth of work written down here. This is a good way to disqualify things off of your list. It’s also a great practice as you can quickly realize you might have 2-3 peoples workloads on your to do list, and then you might need to notify your producer to ask for tasks to be taken off of your plate. For me learning to estimate time more accurately is very important, but it’s also fun. And the more you do it the better you get at judging how long something takes, you begin to realize things go wrong and you compensate for this. The hardest part of having a to do list, is actually marking things off of it. I still do this too, pushing items in my calendar forward a few days after I didn’t get to them the day before. It’s better to learn to schedule tasks more realistically so you know you actually can get these done. A brilliant fiend of mine showed me his productive chart he has, which literally is a chart which outlines each day how successful he was at getting things done day to day. His game was to keep it at 100% consistently, in other words, he would never overburden his day with unrealistic expectations, because he knew it would lower his success rate when he wasn’t able to deliver. |

Setting up Time Constraints

| Timing Your Tasks |

||

| Probably one of the weirdest yet most important bits of advice I can at least suggest for people who are really getting into working more productively. Is to get a stop watch. I own several, and usually have one at my desk at any given time. Whenever I start something, I usually give myself a time to completion. So if I’m doing a shot, I might give myself 2 hours to do it. I’ll set my stop watch to 2 hours, and put it in front of me. This keeps me from getting distracted, and works far better than looking at the clock every 5 minutes. Each time you see the time ticking down it reminds you to get back onto your task, or to focus. Time tends to move slower for me when I’m more conscious about that time is ticking down, so I tend to get a LOT more done this way. It might sound quirky, but I live by this these days.

It also helps you work with estimating how long your tasks take to do, if you are finding you think a shot is going to take 3 hours to do and it takes 6, then it will help you realize this and better gauge your estimates better, which helps when you agree to do something, how long it actually will take you to do. It’s been something I’ve done for probably two years now, and it’s changed my life. I’ve been hesitant to really mention it to people as it seems a little odd, however now a lot of colleagues of mine are doing exactly the same thing, and getting more work done.

|

| Setting Productivity Reminders |

| If you like that one, then also try this – set a reminder either on your phone or google calendar, or whatever you feel like, at set times of the day, that you find you tend to get distracted and start checking your email. Set these reminders to be whatever you want, whether it’s “get back to work” or “are you working?” the idea is that at certain times of the day, your energy drops and you start to lose concentration, even if you are working, you might just be clicking away and going down the wrong path. By setting little reminders it allows you to be more conscious of this, and look at what you’re doing, so for instance spending 20 minutes color correcting your pass you might realize you’re really not being productive and just zoning out, and this at least makes you aware that you need to look at the big picture and get back on track! |

| RescueTime |

| There’s also a cool little app you can purchase called RescueTime, which allows your computer to monitor what you’re doing and at the end of the day/week/month tell you how much time you spend in what application and doing what. Or how productive you were that day based on this. you can also tell it to block distractions (you can specify what is a distraction etc) so that for the next 2 hours or whatever you tell it to do, it will prevent you from browsing websites that are not work related, or loading up solitaire or whatever common things distract you from your work. This can be really handy!

The idea here is not to block you from having fun and literally being tied to a ball and chain. But it is ways to make you more aware of working faster and more efficiently. This way rather than doing OT you can potentially go home early! |

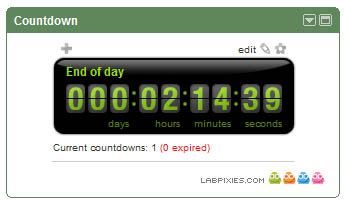

| Work Day Countdown |

| Lastly, I have my igoogle home set up with a widget that reoccurs every day counting down to 6pm. So this is something that I keep on my laptop screen all day ticking down. A boss might look at this and see it as a Fred Flintstone type of dick move, having a clock count down how long you have left each day at work. But actually I use this as a constant reminder that I have X hours, minutes and seconds to achieve all of the tasks I have been assigned today, if I want to get out on time. This helps keep me on track, as each time I see it, I stop messing around and focus on the quickest solution to a problem, rather than trying to find the fanciest.

|

| Early Bird Formula |

| Something I recommend trying, and you will get mixed responses from management, is approaching them to see whether it’s possible for you to trial coming in 2 hours earlier than everyone else each day, and then potentially leaving 2 hours early, provided all of your work is done.

The reason this is suggested, is that notice how when you come into work on a weekend, or stay back at night, you seem to get more done? Because work is less busy, there’s less distractions and less chaos in general. So what if you came in at 8am instead of 10am? Now, when you get in, rather than almost instantly having to check your renders and being whipped off to dailies, followed by chasing up shots and fixes before then lunch, and dozens of other distractions, you actually get to come in early, no one else is there, and sit and review your renders. And if there are errors, then you have time to actually fix those renders and resubmit to the farm before dailies, better yet, in most cases the farm is free at this hour because no one else is using it, so you have the entire farm to yourself to fix these things. And that way you’re able to tweak your work further before the review. But more importantly there are far less distractions, no one is buzzing around or stressing you out, you have time to focus and get things done without the chaos that usually pursues in the mornings. Better yet, traffic is usually much lighter earlier in the day and potentially if you are leaving 2 hours earlier, then traffic is lighter on the way home. Leaving early usually isn’t going to be a problem, as most reviews and meetings are done by 3 or 4 that day, and it’s usually the time of day that peoples energy and productivity begin to sink anyway. However most producers and managers are not going to like this idea, just because there is potential for something to be overlooked if they agree to it. But just sell it to them as something to trial out for 2 weeks and see if you are in fact more productive during that time, and when they see that you are being more productive, push to make it a permanent change. On Superman Returns, myself and another colleague used to try to beach each other to work each morning, at a fairly insane time of 5 or 6 am, because it meant we were in sync with the other studios in LA and Canada, as well as giving us time to get stuff done before meetings and shooting sessions us away. Plus it meant I would feel less guilty about having extended lunches if I wanted to watch a movie at the theater in the public area of the studio… |

| Getting your work right the first time |

| It’s a great approach to do is to begin to learn what the director and supervisor or client wants. If they approve a shot, and they decline another, look at what is different about these, this way if they’re approving several and you notice similarities you can start to hone in on what exactly they like in a shot. Sometimes you might make a really amazing effect or animation, and they really prefer just subtle and less interesting or distracting work as they want the viewers eye to focus on something else. The more you study what this person approving your work likes the more you can get your work approved the first time, and also gain their confidence and opinion if later you want to suggest changes to future passes.

|

| Find what THEY like not what YOU like |

| Recently I worked for a studio in LA and a friend there was having issues with some of his passes not getting approved, and the work looked really amazing but the director kept wanting fixes. So we sat down and rather than looking at the work I decided to go through all the shots and look at what ones had been approved and what ones had been rejected. It became obvious to me fast after realizing most of the ones the director approved were all far simpler and less interesting shots, that really what he wanted was subtlety and he didn’t want kick ass effects that take your eye away from the car zooming past camera, and by looking at what he was approving it was easy to suggest to juts literally dumb-en down your shots, and guess what? they got approved.

This is a huge thing I learned when I was young, was to begin to look at your work from the perspective of the client or producer, rather than as yourself. The more you put yourself in the position of the people who review the final output, and from their perspective whether this is what they would want, rather than what you think is good, the more likely you are able to get an idea as to how it should look. I’ve witnessed artists get emotional and refuse to change their work after there’s been a rather crazy design change to what they’re doing, because they think it will ruin the shot. The truth is, that you’re hired to deliver a shot specifically to what the client requested. So if they want to make this change that you feel isn’t really suitable, then sadly this should be something you need to do without argument. After all you’re being hired to supply a service, the same reason if you were asked to paint a house pink, you’re not going to refuse because you disapprove of the color choice. It’s better to realize this now, a wise bit of advice I was given 20 years ago was “if they have the money, then I sure as hell have the time!” Now keep in mind, if you disagree with the direction they’re going, once the shows over you can always re-render out your work how you like it and throw that through the comp, so you have the look you’re after for your reel. One really interesting thing I noticed when I’m reviewing animation or most peoples work and I want to make sure the motion is correct, is I will tend to review the work either at 6 fps or 60fps. Your eye tends to pick up whether the motion is really real at extremely slow or fast speeds. More so for the higher frame rate, as looking at it too many times at the normal frame rate after a while it becomes impossible to tell the difference, but watching at higher frame rates you tend to pick up whether the motion is really correct or not. |

| Avoiding Distractions & Really Focusing |

| It’s important to consciously be aware of distractions. Whether it’s your girlfriend/boyfriend calling you at work all the time, or the person next to you talking all the time, or even producers/supervisors checking up on you one too many times a day. Or more likely, you browsing the web and sending out emails, or looking at cute kittens doing back flips on YouTube. Identify things that distract you and try to minimalise how often they do. Usually, even if I use MSN or Skype for work, I will close these down while I’m in my zone concentrating When I’m concentrating and people send me links, I tend to open up notepad and copy and paste those links into the window. And throughout the day I’ll add those links in there, and then when I do have some downtime I can look at what people are sending me, rather than either opening it on the spot, or closing the window and not actually seeing whether it was relevant (or a cute fluffy kitten again).

I pretty much carry my Bose QC15 headphones with me everywhere I go. I sometimes go as far as to sleep with them on, especially on flights. They’re comfortable and noise canceling, the sound quality is great and they’re easily portable and very durable. I find now that I concentrate far better with these on, even if I’m just not listening to anything I can have them on to block out 90% of the sound around me, peoples voices disappear and if you’re in a city like New York or Chicago with heavy traffic and constant road work outside your window, then these puppies really help you focus. In addition to this, I wear them a lot when I don’t want to be disturbed as people are less likely to bother you about minute non work related things when you have your headphones on, so there are times of the day I will put these on as a way to prevent people from interrupting me. Much easier than having a do not disturb sign on the back of your head! Other times I’ll shoot those links and other things I need to follow up to my email, and then I can review them on my laptop or phone on my way home. There are times that I need to think about how I’m going to approach a shot, or tackle a lot of stuff, or just plain blow off some steam, and depending on your personality type, some people find it easier to think on their feet, others with their eyes closed etc. I’m lucky that most of the time when I’m working with others I’m able to go lie down on a couch or even the floor without anyone getting upset that I’m not working. Most people are aware that you’re obviously lying down because you’re exhausted or you’re thinking about something, or both. On Priest this would be something I would do a lot, with a pretty loud work environment, I would sometimes go lie down on a couch in another room for 5-6 minutes and think about how I’m going to do a shot, and then come back to my desk with a clear plan, which otherwise I probably wouldn’t have been able to concentrate enough at my desk to do. Other people tend to want to go on a walk, or talk to themselves to help this process, or go into a confined space such as a bathroom stall to think (hey, when you’re under stress we all have our quirky ways of dealing with stress and thought processes!) I’ve spoken to a lot of people about how they tend to concentrate and deal with stress, and these are the most common. Others are listening to classic music and similarly, metal. Talking to yourself oddly can work very positively as you’re able to basically have a discussion about how you want to do something, and essentially trick your brain into giving you some sort of solution. You’re just going to look really weird while you do this of course! The element, is a great book written by Ken Robinson, Ph.D. which describes a lot of really successful artists and individuals and their paths to success, but more importantly the different ways to which we think and learn and apply our individual skill sets. The Element by Ken Robinson, Ph.D. This is one of my favorites, because everyone else seems to adapt to this approach almost instantly after they see it. I tend not to work with high contrast colors. Initially this came from years ago reading that green tends to help you concentrate more, same as with most libraries lamps are green as it’s easier on the eyes and causes less strain. Cooler colors tend to be easier to read and focus with. So whether I’m working on writing a book, or working in 3D, I always change my colors to be easier to work with. So as I previously mentioned, it seems almost viral, people comment my colors are weird, and then I explain to them why, and then within a day most peoples color schemes seem to change as well. Because it makes so much sense, reading black and white just plain hurts the eyes, high contrast colors tend to make it harder to read, which is why people prefer a book lover reading their monitor (I conformed to black and white for this article against my better judgement). |

| Having an Area to Escape to |

||

This isn’t for everyone, but when I moved into my new office one of the first things I made sure I had was a think chair. This ended up being a nice leather massage chair.. but hey it was something I wanted to try out, and it has really increased productivity. There’s a term in NLP called reframing, and it essentially applies to everything. If you’re in a funk, you need to go for a walk to snap out of it, essentially find your refresh button, and look at things from a different perspective. I decided no matter what sort of work I’m doing, I want to have a comfortable area near my desk I can kind of move over to and relax for a minute, out of my work seat and be able to comfortably review my work, think about it and decide a good plan of action. This changed everything, when I was in a bind trying to figure something out.

Some interesting articles related to concentration, productivity and rest are listed below, primarily one from a sleep researcher at Harvard has written an article on sleeping on your thoughts etc. cna help your brain boost productivity by making connections and processing those thoughts more effectively while you sleep. Sleep on it’: Scientific American But this is no news, as to why Google employees amongst many other more successful and radical companies are essentially forming new age siestas Read about – Google Sleep Pods |

| Handling Feedback

|

| Getting stuff approved. Recently I worked at a studio with a friend and his project’s diretor kept sending some of his work back, because this reason or that. Rather than trying to anticipate what the director might respond about next, I suggested we sit down and look at what shots of his were approved and which ones got sent back, and what feedback was said about them etc. This made it really clear very quickly, because I was able to look at the shots the director had approved, and I could tell right away that in those shots,, the effects were much more subtle and kind of simple. Whereas the other ones he was working on, were far more interesting, but definitely made your eye look at them rather than at the car which was meant to be the main focus. So by getting a better feel for what the director/supervisor/client goes for you’re able to anticipate changes ahead of time and make the look specifically what they’re after. Many times I’ve supervised a show and gone “wow this work X artist did looks great! But I know that the director/client is going to want it to be blurred and fluffy and boring” so you’re able to at least anticipate the changes, and the more you work with someone the more you get an understanding for how they work and what they’re going to ask for. So later you will get your work approved on first take rather than fishing for approval.

One of the key things that can get in the way at times is too many reviews. If every day you’re trying to get stuff out for a review, it’s harder to really make much progress. And it’s up to you to politely approach your producer and supervisor and let them know that you are busy trying to get everything done and lets organize an official review later in the week at X time. Until then I want to keep my head down and get everything done. This way you’ve basically freed yourself up to work focused without any distraction however you’ve locked yourself into delivering stuff for that day. By showing people schedules and what you plan to have done by certain dates it will give the more comfort as they know what to expect. At the same time talking in the same language as producers and supervisors is good too – spreadsheets, schedules and shared documents they can keep track of makes you favorable over other artists and shows you can work the same way they are used to. “Speak the producer language” What if you are given requests that you think are a little silly, and from your experience on that project you are pretty confident that they aren’t necessary. Speaking your mind about this is not going to do you any good, however the best way to approach requests that aren’t high priority or are just outright insane, is to just agree to them, but say that you have a lot on your plate to get done first, however once all of these other tasks are done, you’ll look at what is left for the bonus round, and start focusing on getting these additional changes done if time permits. It makes sense to deliver what you’ve originally been asked to do, before you go and spend all this extra time on something that probably isn’t going to be too important, rather than spend all the time on that one task and then not deliver anything at all. Set a cap on peoples changes : When you initially submit something for review, I always urge artists to show variations rather than just one example. This way we can pin point which one might be too much or too little. I always tend to apply the formula of <what they asked for, what you think looks best, and then absolutely too much>. This is a good formula, because if someone says “I want that explosion 10% bigger” and you go and make it 10% bigger, they might say I want it another 10% bigger, and then another, and then another, and then later they realize it’s far too big when they see what originally was. So usually it’s better to show what they asked for, then what you think is good, then one absolutely insanely wrong. So they can see how much is too much, and then you have a set limit of how far you can go with this. Rather than infinitely changing it. Plus the one you show them and the one they designed, they’re most likely going to like one or the other more. So it’s the fastest formula for getting work approved on the first or second take. |

| Communication is important |

| When your renders are complete, shoot an email to your compositor so they know where the passes are, but also CC your producer or supervisor too. This is important, as this way every one’s in the loop, and if your compositor for whatever reason doesn’t get around to comping your work, you are in the clear, as you did in fact submit your stuff, and everyone was kept in the loop about this. This can be really important. Also when you do submit your renders, spend an extra minute or two to compile a quicktime of your render passes, if your farm isn’t set up to do that automatically already. And that way if a supervisor or producer wants to view your pass, they are more likely to do so if they just need to click on a quicktime, rather than trying to load an image sequence up which they’re less likely to do. Do this, as then they’re able to see your work and know where it’s at, and if it’s for some reason comped incorrectly, they know what your passes look like. This is to cover your ass, just in case for you’re working with someone a little devious and wants to push the blame onto you for something they haven’t done or mistakes they’ve made. Which believe me, does happen.

At the same time, check your renders before you submit them to your compositor. As I just mentioned, in some situations your compositor might be too busy or just not get around to comping your stuff. So if you assume that you’ve sent your renders to them and your job is done, think again. It takes 5 minutes to check your renders to make sure they work, but if you don’t, and they assume your passes are fine, and then when they go to comp them on the last day of a job, and your alphas are all wrong, or you just plain rendered your shot from the wrong camera, then you’re to blame for this and you’ll have no time to fix it. So check your renders before sending them to the compositor. And then you have time to fix these errors before anyone else gets to see them! Part of my process is usually I try to finish my day at 5:30 instead of 6, and I spend the last 30 minutes writing emails I need to, to producers and others. I also plan my day for tomorrow while it’s all fresh in my head. And I also send an email to the compositor, producer, supervisor about where my passes are, and the status of my work. This is good because it covers your ass by showing people what you’ve done that day, and also might save you getting called into work at 3 in the morning because they can’t find your render passes. The better you communicate with everyone the easier life will be. I also will usually mention what I’m planning to do the next day. This way if there are some higher priorities, they can let me know before I start in the morning. It also shows initiative, so again people will appreciate how you work. No one is ever going to complain about getting an email from you with important information like this, if they don’t want to read it, they can delete it, but they’ll definitely appreciate it! All of this will be appreciated and show a lot of incentive, it also means that in the rare situations that you do work with people who aren’t doing their job, and want to lay the blame on you then your ass is covered. There’s nothing negative that comes out of this, and usually takes up just a few extra minutes of your time. During rounds, or dailies, if you get feedback on something, usually there’s a production assistant or vfx coordinator around taking notes, otherwise ask the vfx sup or whoever is giving these changes to email you directly with what they just said. “Cool, can you email me what you just said?” It’s important to do this, as then if they tell you to make drastic changes to your work, if they then have to email you – it will give them a second chance to really think about what they’re saying while translating it into an email, because sometimes comments are made on the fly and later they just plain don’t make sense. But also it gives you a second chance to interpret what they are saying, in case you actually had a completely different idea in your head of what they wanted based on your discussion. So this is a good chance to double check that you are both on the same page. Lastly it covers your ass if you are going to go make drastic changes and they say it’s not what they actually asked for, then you can refer to the email as to what you were asked to do. Some of these things might seem like a lot of extra work, but try them out, honestly they will take a few extra minutes of your time and become second nature after a while, however they will help you to incorporate them into your process without thinking, so you become more and more responsible, organized and productive without much thought or effort. |

| Reevaluating your workload |

| It’s also important not to take on too much work, so if you think you’re being given too much work, rather than just thinking you’ll deal with it, and trying to get it all done and risk later realizing it’s far too much to handle. It’s better to raise your hand now and let them know that it might be too much. In most cases a producer or coordinator or such probably doesn’t know how long a task is going to take, and they’re waiting for you to agree or disagree to the task. after all, you are the one doing it. So if you think it’s too much for you to handle, tell them rather than waiting until it’s too late to say you can’t in fact do it. Which does happen, and screws everyone.

I’ve gone as far as to say I do not have time to do my time sheets or go to the post office or to lunch etc. and had other people take care of these tasks for me, because in the greater picture, those small distractions are less important than me delivering a shot. Now of course I’ve approached these issues in the correct way, but if you are doing a high priority task, it isn’t necessarily a bad idea to see whether other things that might get in the way can be handled by someone else so you can keep productivity up. Same goes if you are under resourced, you might need more computers to deliver your work – it’s better to let people know this so they can accommodate it. Or if you have minor tasks that other artists can take on, such as exporting your stuff to FBX for the compositor, and converting your passes or transferring files etc. If you have more important things to do, evaluate whether you’re the best person to be taking on the smaller tasks, it’s not being lazy it’s being efficient. And as I mentioned before, communication is key here, keep everyone in the loop. |

In Closing

|

| This article has been really fun to write, and I’ve been wanting to write it for a little over two years now. The idea behind it is simple, look at how you are doing your work and try to see if there is a more practical way to do it, brute force isn’t always the way – and overtime can be detructive rather than constructive.

Writing the second half of this article has been a lot more difficult than the first, part 1 was aimed purely at the way we work and what works and what doesn’t. Party 2 is much more focused on ourselves and really taking responsibility for getting work done, and looking at ways to expand and at least motivate people to go out there and find ways they work more effectively. I originally collected most of these notes over the past two years, as I’ve become quite OCD about monitoring successfully and destructive patterns with pretty much every type of way I work, but recently I started to put this together and realize there’s literally too much to fit into one article without it become too big to bare. So I’ve just put in here a select few approaches to day to day work that I think are applicable and that yield the most positive results. Most of what I’ve covered here are the approaches that I’ve shared with others and seen others be able to practice time and time again, and not everything in here will be useful for everyone, however hopefully you will be able to select some practices that will apply to what you do and help improve your productivity overall! -Allan McKay Los Angeles, CA January 2011 |

Overtime Vs Productivity 01

Is it worth it working extreme hours all the time, day in day out – more importantly are you actually getting that much done during that time?

Foreword

This article isn’t a stab at the industry, nor should it be perceived as such. It’s actually a 2 part article which looks at how people, both from the management side and from the artist side work and why we get burned out, ways to avoid this and hopefully inspiring some to reevaluate how they work. I personally think that there’s two sides to the coin, and although a lot of the time management could work a bit better on making sure artists are appreciated for their efforts when they are killing themselves to deliver a deadline, artists too can look at bettering their efforts in terms of communication and self management, and even just raising their hand when they think something mightn’t be delivered on time, rather than waiting until it is in fact too late to do anything about it. The industry itself is pretty shaky right now, both with work being outsourced to other countries, and forcing studios in the US and other countries to underbid to actually be awarded a show, which then reflects back onto artists needing to double their efforts to deliver the same amount of work in a less amount of time to compensate for this.

I want to mention this, as I’m not bitter, or have any grudge the vfx industry as it stands, I work both as an vfx artist, client and producer so I’ve been on every each end of the stick. But I do believe it’s an interesting topic and I’ve wanted to discuss this for some time. Currently I’m in the middle of putting together the VFX Artist Insight Series which while filming this across the US in San Francisco, Los Angeles, Las Vegas, New York City and other cities I’ve spoken with many artists and it’s really been interesting discussing topics such as this, and some of the current events that are happening that relate back to this. So I definitely think it will be interesting not only to write about this, but also to hear from all of you about your insights into this as well. I have so many talented and smarter people than myself visiting my web site on a daily basis and I’m sure a lot of you will be able to share some of your own insight onto the subject as well! But if not, then I at least hope you take something away from this.

Overtime vs Productivity

Working in the VFX Industry the one thing we can all associate ourselves with is working too much overtime. People constantly burn out, either temporarily or permanently. Others lose it during a project and storm out…

I’ve witnessed plenty of relationships and divorces occur, and most people sick for weeks after a long form project. The thing is, can this actually be avoided? Do you really need to work all of those late nights to deliver your work? Most of the time it’s management wanting artists to burn the candle at both ends to deliver a project. In some cases it makes sense, to save your energy until you reach the finish line and then you gun it as hard as you can to achieve your desired goal. However, there are plenty of people who make the call too soon, and start getting people working late nights when it’s not necessarily called for, such as mid way through a project, rather than when it’s absolutely necessary. And then what happens, you are literally burned out when you actually are at the crucial point.

The truth is that everyone does it, whether you’re a client, manager, producer, supervisor or anyone managing people, you put them through the extra yards to get extra work out of someone for usually no added cost. I mean, if you get an extra 5-10 hours a week out of each of your staff mid way through the project, then that surely means that toward the end of the show you’re going to be days or weeks ahead of schedule right?

The downside is that when people begin to burn out, they lose focus. They begin to make mistakes and fail to concentrate at the pace they should actually could work at. Some get bitter, others just lose any real care for doing their work.

I remember one movie I worked on where I was literally working 145 hour weeks literally living & sleeping at the office, and at the end of the day pretty much getting nothing done. Probably what would have made more sense is working normal hours and actually getting a chance to catch up on sleep, as well as process mentally the tasks I needed to solve. Rather than being so busy trying to get things done and try to concentrate when it felt nearly impossible to see straight, eyes stinging and ears ringing (seriously) that the work I did produce was probably about 10% what I could be producing. I like to think one of the most common issues that comes up is human error, people make mistakes. People take things for granted, miss bits of information they need and have their mind elsewhere and then, make mistakes. However, if they’re well slept, and able to concentrate, they’re less likely to make mistakes. There are plenty of additional things they can do themselves to manage themselves better, and I will get to that at a later time – but when it comes down to it, the less burned out and tired, stressed and used up you feel the more likely you’re able to keep your eye on the ball and do good work.

Recharging and revitalizing

At the same time, if you’re extremely happy, charged and into the work you’re doing, you’re going to care even more and do even better work! So getting appreciation from your peers and seniors, as well as acknowledgment for your good work helps to do this. Just the same if you’re taken out to lunch or other events to help you recharge and also solidify your team better. Taking a Friday afternoon off to go out for some drinks and give everyone a chance to recharge, not only boosts morale but gives everyone a chance to talk with each other and let ideas fly. Taking people outside of their work environment resets their brains enough to start thinking about new things to try and ways to work together. The same reason most business is done over drinks, everyone loosens up and you’re given time with your co-workers to sit in the sandbox and play a little, without needing to have your eye getting something done.

One of the most common mistakes I see, which falls more on the artist – is that people are so busy trying to get their work done, they’re not looking at the big picture, and they’re not looking at whether the direction they’re going is the right one and any possible issues lingering that they’ve overlooked. I honestly think that 99% of most visual effects work you can do sitting under a tree with pen and paper, the same reason I love planes/airports and theaters so much – because it gives me a chance to reset my brain and start to think about my work without physically doing it and narrowing my ideas through false progression. So many people are busy trying to get the work done, that they head down the wrong path and not only do not realize this until much later, but only once they finally are at the point of realization that they have made so many mistakes, that they cannot actually backtrack very easily. But when the pressure is on, and you’re overworked, it’s much easier for this to happen as you’re under too much pressure and limited time to actually question yourself whether what you’re doing is ultimately the best solution?

Another example of burning people out midway through a project, the earlier things begin to be finalized.

The earlier in a show things are pushed to be finalized the more leeway and room for changes. I’ve sat in shows where I’ve completed my tasks sufficiently, however then more unnecessary tasks have come up, rather than moving onto the next stage in the process, purely because there’s time to do it “oh cool, ok well lets try this and this as well, you know, just in case they decide to go down that path, or something” Again this too can be pushed onto the artist and everyone really, to look at the big picture, but preparing and getting a project out the door should be on every one’s mind from the beginning, rather than the last 30% of the schedule when everyone begins panicking how they are only 15% into the actual project’s completion. Looking at the big picture allows for people to push to get things signed off sooner, and get more of the project as a whole done, and fill in the blanks later where necessary. Later revisit those bits for sign off. Some clients are the major fault here, and they see it as having too much time, so they start making changes that aren’t needed. Why do you think on most projects everything gets finalized and approved in the last week? Of course it’s because most of the work is finished by then, but also at that stage people are forced to make decisions and sign off on the studio, and your work. So is it really worth killing everyone mid way through a project when it’s clear the client isn’t in fact making any real decisions until the last quarter of the schedule.

Konami – “Dark Nekrafura”

A great example of this was a Konami project I did in Sydney 10+ years ago, where the client was notorious for having the entire team work the entire 48 hours or so of the end of the project, when they literally come in and make changes in person. They would literally come in from Japan with 15 or so people, take it in shifts art directing our artists, taking turns as each other slept in a non going wave of changes, and in some cases even try to ask if they can supply a completely new script and concept, or new features that were never ever discussed in the month of production leading up to then.

This was common with this client, and it was one of the type of projects artists would try not to get put on because it had such a potent burn out rate (this was actually the last Konami project we ever did before finally thanking them and asking them to find a new studio, as it was particularly brutal this one time). But because we knew how they worked, we were expected to go about our days and not really do any overtime, just do the changes and work the hours we were expected, because we knew everything would probably change once they actually arrived – they were pretty notorious for simplifying a lot of the concepts and animation, perfectly articulated tiger crawling through the jungle then became flying tiger with no body movement and glowing red eyes. “ok, cool, delete all key frames, add glow, goodbye last 2 weeks of work”. Rule of thumb with this client was to “increment on save” because you’ll probably go back to version 01 out of the 500 you have, and they will instantly approve that one on first go.

So in a way we knew what was asked of us, do your job, don’t burn out, and don’t work yourself too hard, because you WILL be required to work crazy hours the last 3 days of the job, let your husband/wife know too so they mark it on the calendar you’re “out of town” for 3 days.

Superman

One of my fondest projects I’ve ever worked on IS in fact probably one of my most ridiculously tight deadlines I’ve ever had to endure. What made it different was that on Superman Returns we had 3 weeks to recreate the entire opening sequence to the movie.

One shot, all CG, 2.5 minutes, 3 weeks to do it. However what was different about this was that I felt like we didn’t really make any mistakes at all on this project. We had a solid crew of people and we had a plan. I was lucky and managed to hit all the right points, getting my initial look for the core of the sun exploding approved first go, and told to proceed and essentially just do whatever it was I was doing. But I also was given the support I was by management to keep me going, rather than putting too much pressure on me, I was given talented and pretty much genius people to take the more redundant parts of my job away from me to focus on building the effects I needed.

At the same time, management – although was applying pressure as we did need it, and they too were getting pressure from Warner Bros. they focused on helping us take our minds off the stress by making work fun. I haven’t really ever seen the President of a vfx studio at 3 in the morning walking around with a blender full of margaritas, or taking all the guys and girls out for Mexican, tiki bars and then a trip to a gentleman’s club some nights (despite how this might be perceived, both the male and female staff would all go along and it was quite an amusing environment to have some drinks in). Encouraging gags and letting people joke around and leave when they needed to, and the rest of the time keep out of our way rather than making us feel like we need to work harder. This is still one of my fondest projects to have worked on, also one of the more stressful, however I was never bitter, and I also think that I did some of the best work I have ever done on this project because we were managed so well.

I did get sick for 2-3 weeks after the project, after all, my mune system totally crashed from lack of sleep. And this isn’t healthy. And there were people who did respond negatively to the project and pressure, but everyone has their breaking points. The fact we were paid hourly rather than a day rate meant I never got bitter or felt like every hour extra I worked, was essentially an equation as to how many dollars less per hour I actually am earning that day. Instead I was able to use a calculator at 6 in the morning to work out how much money I earned that day and feel good about going back to my hotel for a couple of hours and returning at 10am to start a new day.

This is what made it different! We were compensated for our time, and better yet, we felt appreciated for the work we were doing. The environment was fun and people were making the right decisions in regards to what we needed to get done, so we could focus on our work. If at any point I felt like we had wasted a day or a week because of a bad call or decision, I would have lost it. But we were guided in the right direction and left to do what we did. Everyone knew each other on the project, which made it work much better too. We all had a familiarity with each other, and knew our strengths in the workplace, we were all fond of each other and we were all able to communicate, rather than wait for meetings to feel like we need to talk. People could joke or tell stories while we all laughed and continued our work, or help each other out when we got stuck. Because we all were actively going out and having a beer or spending time together relaxing and we were therefore comfortable doing all of this. Which is a key factor to making this all work.

At the end of Superman, the VFX Supervisor who had recently bought a bus company, gave us a bus we could drive to Vegas in. The owners put us up in Vegas for free, and organized loads of events for us there. We stocked the bus full of booze and went alongside the production team from Warner Bros to Vegas, drinking the entire trip. We fired machine guns (well I and a few others did, everyone else was too hungover), Cabaret shows, big dinners, gambling, you name it. It was a chance to relax and celebrate what we had accomplished. We got vfx crew shirts, and we all got to drive back on the bus hungover beyond all hell two days later. This did make the trip, getting a chance to relax, it was a light at the end of our tunnel. And we didn’t feel used up after the show, or worse yet told we need to work late on the next show, days after this one had wrapped (which I’ve seen all too often). During Superman I did witness one divorce personally, and heard of plenty more that had happened at other studios working on the film.

The industry and where it currently stands

The visual effects industry can be very shaky, and a very competitive industry, at the same time making bad calls on bidding, or worse underbidding to be awarded a show can mean that rather than tighter calls on changes etc. Artists just need to work more hours to handle the workload.

I find at times, artists being compensated hourly is great, because it means they are being paid for the hours they work, and are more happy to work the additional hours when they need to rather than being bitter or fighting it. At the same time, it forces management to be more careful with artists working OT because it actually does cost them money. Essentially everyone is paid the amount they’re owed and they can feel more appreciated knowing that they aren’t essentially having their life sucked out of them, and for free. However, that isn’t always possible. And it’s not because of a job is severely underbid, there can be many reasons. Everyone needs to eat, and just turning jobs down because the client obviously isn’t willing to spend the money is going to still lead to studios pockets emptying if they do not take on work. But that doesn’t mean they can’t still try to compensate with a more positive work environment and a show of appreciation for the artists.

An example of semi-successful handling OT

I produced a commercial probably 2 years ago, where the budget was tight, but the deadline was even tighter. 3 weeks to complete a pretty ambitious commercial, I hired another studio to help out with the commercial just so I knew we would have the support we need, however their work wasn’t really as up to par as I expected and they ended up costing more than half the commercial for work we later had to redo. I had a core team of artists on the show, and they performed miracles. They literally killed during this time, performing amazing work and literally saving the day. We had 3 weeks, and I knew there was going to be a ton of overtime, and that wasn’t in the budget. They knew that, I warned them before they came on board. So it wasn’t news to them, and they were all prepared to do it.

However, even though I was VFX Sup’ing the show and wasn’t hands on as an vfx artist, I did stay back late every night to ensure that A) they had everything they need and if a decision was needed to be made I was there to make it and B) for morale so I wasn’t at home snug in bed or watching tv while they were slaving away, rather I was there and helping them wherever I could. Each night I would take them out for dinner, maybe a beer or two but I would warn them not to overdo it as we had to work, but there were times where we’d end up bringing some bar staff (girls obviously) back to our studio to hang out if we had a late dinner, and we balanced having a life and fun with getting the work done. More importantly I made sure they were being taken care. A $40 meal per person isn’t that expensive compared to them working an additional 7 hours that night, I don’t really understand studios who do expect you to work hideous amounts of overtime and not compensate you with a meal, or a taxi home late at night. At the same time if they were to sleep at the office, which unfortunately on this one project it did happen a few times – I would always call my producer on his way into work to bring breakfast in for everybody.

Again such a small thing, but it always went a long way. At the end of the project, again I took everyone out for a very expensive meal and a night of drinks, I was very grateful for their work and also ensured that any future employers knew of this too. I was glad to hear everyone say it was the best team/project and management they had worked with, ever. And I think it was more just the fact that if they aren’t being paid at least they are being treated like human beings and not like machines. I mention this as it is proof that if you are going to make people work late, it’s not the end of the world but you do need to make sure they are appreciated, and compensated as such.

Artists under pressure

People under pressure are more likely to snap, crazy deadlines and depressing work environments lead to people panicking, hating work, not thinking clearly, avoiding talking with management or showing their work in fear of bad responses. There are plenty of reasons and a lot of effects to this. Some people when yelled at, respond well they buckle down and do the work, most however freeze. I’ve seen this even on recent projects I’ve seen artists literally stop what they’re doing for a day because the pressure is too much, most of the time it’s purely all in their head, and this is something I will cover in chapter 2 – but never the less people do freak out and become counter productive. People deal with stress in many different ways, but there are plenty of support people can be given as well as positive feedback to go with the negative to help keep everyone on track.

What is clear is that it is sometimes necessary, not every job has the budget, or there might be other circumstances. However carefully planning projects, asking artists if they are comfortable with their workload and getting others involved will allow for better scheduling of workloads. However more importantly, pushing artists to work too much overtime when it’s not needed can be extremely counter productive when they then begin to make mistakes and slow their pace, mess up and lack the energy to really care anymore, or communicate/play well with others. This ends up making the schedule fall further behind, than if they were well rested and inspired to work faster. Some of the best producers I worked with in my early career literally got into what you were doing, learned how to load a RAM player to view some videos, so they weren’t waiting for you to come in in the morning to show a client a video, they were able to go an extra step to run and get you a coffee or pay a few bills online, or at least have someone else do these things, move your car etc. which sounds extreme, but if you really look at it, it actually keeps you at your desk working, rather than losing time doing these things, and for you it’s one less thing to stress about. Everyone wins, maybe even management more than the artist really. So those little things are just the tip of the iceberg but essentially it’s a good way to keep your machine all lubed up and ready to rock, rather than having minor breakdowns and halts as it functions.

I would be very interested in hearing others insights as well as situations they’ve experienced. I’m not looking to have negative comments or complaints and comments, I’m looking for productive insights into projects people found to be successful and why, or where shows or productions could have been handled more efficiently. As I stated in the foreword, this isn’t a counter productive article, it’s purely an insight into something I strongly believe, that overtime really is counter productive, and the more people all mesh together and calibrate each others work flow to make sure everyone is working efficiently the more things get done efficiently.

The Flip Side – Chapter 2.

So the flipside to this is the fact that although there are good and bad work environments, and managements do have a lot of influence on how much you are going to work – artists are just as responsible for working long hours and burning out. That being said a vast majority of people out there do tend to want to be lead and do not want to seek responsibility for managing themselves and making themselves more efficient through coming in on time, staying focused and communicating and managing the workplace as much as the workplace manages them. But ultimately you are responsible for what you do and do not put up with, and you are also responsible for raising a flag if you think some schedules are unreasonable. It’s better for people to be aware of it then and there and re-coordinate resources to compensate, rather than you taking it on the chin and then later not delivering and saying it was because the schedule wasn’t fairly placed.

A lot of this comes with experience, and a lot of this can be argued. But there is plenty YOU can do on your end to avoid working unnecessary overtime, and helping yourself work more efficiently. I will be following up on chapter 2 of this article shortly!

-Allan McKay

New York City, November, 2010

Allan McKay is an award winning Technical Director & VFX Supervisor, working in visual effects for Hollywood films for over 15 years. Also a Public Speaker & Author. Teaching master classes at events such as siggraph and for Autodesk and other events all around the world.

Allan has previously worked for studios such as Industrial Light + Magic, Blur Studio, Ubisoft and many others and was awarded as an Autodesk Max Master as well as working on dozens of projects that either received or were nominated for Emmy and Oscar awards.

McKay lives in Los Angeles, CA and is the director Catastrophic FX film studio.

Sidekicks

Coca Cola Heist

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bSNCnyCUdk8&w=640&h=390]

Harry Potter and The Half-Blood Prince

The Last Minecart

Digital Magazine Motion Cover

Minecraft Diamonds

Ultimatte in Nuke Tutorial by Steve Wright

Nuke 6.3

Back to the Future

"Back to the Future," Einstein Jump

Real photographic background plate of Delorean, with glows and time slice animation created by the animation department at Industrial Light & Magic.

Real photographic background plate of Delorean, with glows and time slice animation created by the animation department at Industrial Light & Magic.  The fire and sparks (and their reflections) were created on the set with special effects rigs attached to the Delorean.

The fire and sparks (and their reflections) were created on the set with special effects rigs attached to the Delorean.

A large strobe light on location provided bright interactive light. Full frame flashing was also achieved in the optical composite.

A large strobe light on location provided bright interactive light. Full frame flashing was also achieved in the optical composite.  Hey, look in the upper left corner of the screen. Say hi to the crew!

Hey, look in the upper left corner of the screen. Say hi to the crew!

Panning left with Delorean. The car is actually on the set, with animation and effects added optically.

Panning left with Delorean. The car is actually on the set, with animation and effects added optically.  The pan reveals bluescreen-photographed Marty and Doc. The actors were tracked and matted into the shot.

The pan reveals bluescreen-photographed Marty and Doc. The actors were tracked and matted into the shot.

Pan abruptly stops, explosions and flares optically composited to represent time slice effect.

Pan abruptly stops, explosions and flares optically composited to represent time slice effect.

First visible frame of explosion element. The main explosion element has a faked reflection in the wet ground, achieved in the optical composite.

First visible frame of explosion element. The main explosion element has a faked reflection in the wet ground, achieved in the optical composite.  Explosion element runs backwards, giving the impression of an implosion. On-location, live-action ignition of fire trails appear, and are skip printed to appear to ignite much faster than reality would allow, approximating the feeling of 88mph.

Explosion element runs backwards, giving the impression of an implosion. On-location, live-action ignition of fire trails appear, and are skip printed to appear to ignite much faster than reality would allow, approximating the feeling of 88mph.  Marty's foreground foot is rotoscoped to allow the fire trail to appear behind his leg.

Marty's foreground foot is rotoscoped to allow the fire trail to appear behind his leg.

The last frame of the shot.

The last frame of the shot.  In-camera effect, featuring on-set fire trails, using stunt performers.

In-camera effect, featuring on-set fire trails, using stunt performers.  This shot was skip printed in post production to give the ignition the feeling of greater velocity, giving the impression of the Delorean continuing its 88mph journey in a parallel dimension of time. As a result, the fire's motion is somewhat strobey.

This shot was skip printed in post production to give the ignition the feeling of greater velocity, giving the impression of the Delorean continuing its 88mph journey in a parallel dimension of time. As a result, the fire's motion is somewhat strobey.  Notice the relative exposure difference between this shot and the shots preceeding and following it. In this shot, the cinematographer exposed the film to feature the fire (or was underexposed in the colortiming or visual effects process), which reveals the internal structure of the fire. In the shots before and after, the actors and environment were the target exposure values; consequently, in those shots, the fire is blown out and overexposed, leaving only hot white fire shapes.

Notice the relative exposure difference between this shot and the shots preceeding and following it. In this shot, the cinematographer exposed the film to feature the fire (or was underexposed in the colortiming or visual effects process), which reveals the internal structure of the fire. In the shots before and after, the actors and environment were the target exposure values; consequently, in those shots, the fire is blown out and overexposed, leaving only hot white fire shapes.  The first frame of the iconic Einstein time slice effect, featuring actors Christopher Lloyd and Michael J. Fox. The actors were shot against a bluescreen, standing on a mirror. The mirror gave the effects artists pristine reflections of the actors; the reflections were matted to separate them from the actors, and treated in the composite to appear as wet, pavement reflections by adding displacement and tweaking the brightness.

The first frame of the iconic Einstein time slice effect, featuring actors Christopher Lloyd and Michael J. Fox. The actors were shot against a bluescreen, standing on a mirror. The mirror gave the effects artists pristine reflections of the actors; the reflections were matted to separate them from the actors, and treated in the composite to appear as wet, pavement reflections by adding displacement and tweaking the brightness.  Michael J. Fox's screen right foot was placed behind fire licks via frame-by-frame rotoscoping. Areas of fire were articulated to bury Fox's foot within the fire. Like the previous two shots, the background plate was skip printed to give the fire trails more energy and speed.

Michael J. Fox's screen right foot was placed behind fire licks via frame-by-frame rotoscoping. Areas of fire were articulated to bury Fox's foot within the fire. Like the previous two shots, the background plate was skip printed to give the fire trails more energy and speed.  "What did I tell you?!?"

"What did I tell you?!?"  "Eighty eight miles per hour!!" This shot is entirely in-camera. The fire trails are a practical effect, just like all of the previous shots. In the sequence, the trails have been fully formed, and are no longer being generated; as a result, there was no need to skip print the trails for this shot.

"Eighty eight miles per hour!!" This shot is entirely in-camera. The fire trails are a practical effect, just like all of the previous shots. In the sequence, the trails have been fully formed, and are no longer being generated; as a result, there was no need to skip print the trails for this shot.

Waterman vs. Sandman

Hereafter

Nukepedia

http://www.nukepedia.com/ Downloads, articles and info – all about Nuke. Gillian Benard

NFXPlugins

The current version of NFXPlugins 1.0v1 contains 25 separate nodes for The Foundry's Nuke compositing application.

- N_Add – image filter

- N_Align – transformation

- N_Clamp – image filter

- N_Colorize – image filter

- N_Compress – image filter

- N_DuoTone – image filter

- N_Expand – image filter